Математические формулы в LaTeX

Одним из главных мотивов для Дональда Кнута, когда он начал разрабатывать исходную систему TeX, было создание чего-то, что позволяло бы просто записывать математические формулы, но при этом выглядело бы профессионально на этапе печати. Тот факт, что ему это удалось, скорее всего и был причиной того, что TeX (а позже и LaTeX) стал настолько популярным в научном сообществе. Возможность набора математических формул — одна из самых сильных сторон LaTeX. Но при этом, это очень объёмная тема из-за существования большого количества математических обозначений.

Если для вашего документа требуется всего несколько простых математических формул, обычный LaTeX предоставит вам большинство инструментов, которые вам смогут понадобятся. Если же вы пишете научную статью, содержащую множество сложных формул, пакет amsmath привносит некоторое количество новых команд, которые являются более мощными и гибкими, чем те, которые предоставляются базовым LaTeX. Пакет mathtools исправляет некоторые причуды amsmath и добавляет полезные настройки, символы и окружения в amsmath. Чтобы использовать любой из данных пакетов, включите в преамбулу создаваемого документа:

\usepackage{amsmath}

или

\usepackage{mathtools}

Пакет mathtools загружает пакет amsmath и, следовательно, нет необходимости указывать \usepackage{amsmath} в преамбуле, если используется mathtools.

Математическое окружение

[править]Системе LaTeX необходимо сообщить, когда текст, который вы вводите, является математической формулой. Это необходимо из-за того, что LaTeX набирает математическую нотацию иначе, чем обычный текст. Поэтому для данной цели объявлены специальные окружения. Их можно разделить на две категории в зависимости от того, как они представлены:

- text - текст формулы отображается прямо в строке, внутри текста, где он объявлен. Например, я могу написать формулу прямо в этом предложении.

- displayed - для отображения формулы в отдельной строке.

Поскольку математические формулы требуют особых окружений, естественно, есть их соответствующие названия, которые вы можете использовать стандартным способом. Однако, в отличие от большинства других окружений, есть удобные сокращения для объявления ваших формул. Следующая таблица объединяет информацию о них:

| Тип | Встроенная (в текст) формула | Выключенная (на отдельной строке) формула | Выключенная формула с автонумерацией |

|---|---|---|---|

| Окружение | math

|

displaymath

|

equation

|

| Сокращение LaTeX | \(...\)

|

\[...\]

|

|

| Сокращение TeX | $...$

|

$$...$$

|

|

| Комментарий | equation* (версия со звездочкой) убирает нумерацию, но требует использования amsmath

|

Внимание: Следует избегать использования $$...$$ , так как это может вызывать проблемы, особнно с макросами AMS-LaTeX. Кроме того, в случае возникновения проблем сообщения об ошибках могут оказаться бесполезными.

Окружения equation* и displaymath являются функционально эквивалентными.

Если вы набираете текст в обычном режиме, говорят, что вы находитесь в текстовом режиме, но когда вы печатаете в одной из этих математических сред, вы, как говорят, находитесь в математическом режиме, который имеет некоторые отличия от текстового режима:

- Большинство пробелов и разрывов строк не имеют никакого значения, поскольку все пробелы либо получены логически из математических выражений, либо должны быть указаны с помощью специальных команд, таких как

\quad - Пустые строки не допускаются. Только один абзац на формулу.

- Каждая буква считается именем переменной и будет набрана как таковая. Если вы хотите набрать обычный текст в формуле (обычный вертикальный шрифт и нормальный интервал), вам необходимо ввести текст с помощью специальных команд.

Вставка "выключенных" математических формул внутри блоков текста

[править]Чтобы некоторые операторы, такие как \lim или \sum , правильно отображались в некоторых математических окружениях (имеется ввиду$......$), может быть удобно написать класс \displaystyle внутри окружения. Это может увеличить длину строки, но приведет к более правильному отображению показателей и индексов для некоторых математических операторов. Например, $\sum$ напечатает маленькую Σ а$\displaystyle \sum$ напечатает большую , как в уравнениях (Работает только при включенном пакете AMSMATH). Можно принудительно настроить такое поведение для всех математических сред, объявив \everymath{\displaystyle} в самом начале (т.е. до \begin{document}).

Математические символы

[править]В математике существует достаточно много различных символов! Ниже приведены те, к которым можно получить доступ прямо с клавиатуры:

+ - = ! / ( ) [ ] < > | ' : *

Помимо тех, что перечислены выше, для ввода некоторых символов могут потребоваться отдельные команды. Это требуется, например, для ввода греческих букв, символов множества и отношений, стрелок, бинарных операторов, и т.д.

Для примера:

\forall x \in X, \quad \exists y \leq \epsilon

|

|

К счастью, есть инструмент, который может значительно упростить поиск команды для определенного символа. Найдите "Detexify" в разделе external links ниже. Другой вариант - посмотреть "Полный список символов LaTeX" в разделе external links ниже.

Греческие буквы

[править]Греческие буквы довольно часто используются в математике, но их достаточно просто набирать в математическом режиме. Вам просто нужно ввести название буквы после обратной косой черты: если первая буква названия строчная, вы получите строчную греческую букву, если первая буква названия заглавная (только первая буква), тогда вы получите прописную букву. Обратите внимание, что некоторые заглавные греческие буквы выглядят как латинские, поэтому они не предоставляются LaTeX (например, заглавные буквы Alpha и Beta это просто латинские "A" и "B" соответственно). Строчные буквы эпсилон, тета, каппа, фи, пи, ро и сигма представлены в двух разных версиях. Альтернативная (variant сокр. var) версия, создается добавлением "var" перед названием буквы:

\alpha, \Alpha, \beta, \Beta, \gamma, \Gamma, \pi, \Pi, \phi, \varphi, \mu, \Phi, \varPhi

|

|

Прокрутите вниз до #Список_математических_символов чтобы увидеть полный список греческих символов.

Математические операторы

[править]Оператор - это функция, которая записывается с помощью слова: например, тригонометрические функции (sin, cos, tan), логарифмы и экспоненты (log, exp), пределы (lim), а также след и определитель (tr, det). В LaTeX многие из них определены как команды:

\cos (2\theta) = \cos^2 \theta - \sin^2 \theta

|

|

Для некоторых операторов, таких как Предел, нижний индекс помещается под оператором:

\lim\limits_{x \to \infty} \exp(-x) = 0

|

|

Для оператора Сравнения по модулю существует две команды: \bmod и \pmod:

a \bmod b

|

|

x \equiv a \pmod{b}

|

|

Чтобы использовать операторы, которые не определены заранее, например argmax, см. [[../Высшая математика#Определяемые операторы|определяемые операторы]]

Степени и индексы

[править]Степени и индексы эквивалентны верхним и нижним индексам в обычном текстовом режиме. Символ каретки (^; так же известный как циркумфлекс) используется чтобы что-то поднять, а нижнее подчёркивание (_) для опускания. Если необходимо повысить или понизить выражение, содержащее больше одного символа, его необходимо сгруппировать с помощью фигурных скобок ({ и }).

k_{n+1} = n^2 + k_n^2 - k_{n-1}

|

|

Для степеней, состоящих из более чем одной цифры, заключите степень в {}.

n^{22}

|

|

Подчёркивание (_) может использоваться с вертикальной чертой () при использовании выражения в качестве нижнего индекса (это предложение требует уточнения):

f(n) = n^5 + 4n^2 + 2 |_{n=17}

|

|

Дроби и биномы

[править]Дроби создаются с помощью команды \frac{numerator}{denominator}. Так же и Биномиальный коэффициент можно записать используя команду \binom:

\frac{n!}{k!(n-k)!} = \binom{n}{k}

|

|

Дроби можно помещать одну внутри другой:

\frac{\frac{1}{x}+\frac{1}{y}}{y-z}

|

|

Так же обратите внимание, что при встраивании дробей в строку текста или записи одной дроби внутри другой, , их отображаемый размер должен быть заметно меньше, чем в выключенной формуле. Команды \tfrac и \dfrac позволяют использовать стиль записи соответствующий использованию \textstyle и \displaystyle. Точно так же работают команды \tbinom и \dbinom, записывающие биноминальный коэффициент.

Для относительно простых дробей, особенно внутри текста, может быть более эстетично использовать Степени и индексы:

^3/_7

|

|

Данная запись может показаться немного "растянутой" (занимающей много места), сжатую версию можно определить, вставив некоторое отрицательное пространство.

%running fraction with slash - requires math mode.

\newcommand*\rfrac[2]{{}^{#1}\!/_{#2}}

\rfrac{3}{7}

|

|

Если вам необходимо часто использовать подобную запись дробей в своём документе, рекомендуем использовать пакет xfrac.

Данный пакет поддерживает команду \sfrac для создания наклонных дробей.

Использование:

Take $\sfrac{1}{2}$ cup of sugar, \dots

3\times\sfrac{1}{2}=1\sfrac{1}{2}

Take ${}^1/_2$ cup of sugar, \dots

3\times{}^1/_2=1{}^1/_2

|

Если в качестве показателя степени используются дроби, необходимо использовать фигурные скобки вокруг команды \sfrac:

$x^\frac{1}{2}$ % no error

$x^\sfrac{1}{2}$ % error

$x^{\sfrac{1}{2}}$ % no error

$x^\frac{1}{2}$ % no error

|

|

В некоторых случаях добавление только данного пакета может привести к ошибкам о том, что определённые формы шрифтов недоступны. Тогда необходимо так же добавить пакеты lmodern и fix-cm.

В качестве альтернативы, пакет

nicefrac предоставляет команду \nicefrac использование которой аналогично использованию \sfrac.

Непрерывные дроби

[править]Непрерывные дроби следует записывать с помощью команды \cfrac:

\begin{equation}

x = a_0 + \cfrac{1}{a_1

+ \cfrac{1}{a_2

+ \cfrac{1}{a_3 + \cfrac{1}{a_4} } } }

\end{equation}

|

|

Умножение двух чисел

[править]Чтобы сделать умножение визуально похожим на дробь, можно использовать вложенный массив, например, умножение чисел, написанных одно под другим..

\begin{equation}

\frac{

\begin{array}[b]{r}

\left( x_1 x_2 \right)\\

\times \left( x'_1 x'_2 \right)

\end{array}

}{

\left( y_1y_2y_3y_4 \right)

}

\end{equation}

|

|

Корни

[править]Команда \sqrt создаёт символ квадратного корня, окружающий математическое выражение. Он принимает необязательный аргумент в квадратных скобках ([ и ]) для изменения показателя (степени) корня:

\sqrt{\frac{a}{b}}

|

|

\sqrt[n]{1+x+x^2+x^3+\dots+x^n}

|

|

Часто для написания корня люди предпочитают делать его "закрывающимся", когда заканчивается подкоренное выражение. Это позволяет более точно определиять границы верхней линии при чтении. Хотя обычно при печати формул на компьютере этим пренебрегают, LaTeX позволяет записывать корни таким образом. просто доабвьте следующий код в преамбулу Вашего документа:

Этот код сначала заменяет команду \sqrt на \oldsqrt, после чего переопределяет \sqrt, используя стандартный корень, сильно его дополняя. Вы можете увидеть пример использования нового стиля корня на картинке слева и сравнить его со старым видом на правой картинке. К сожалению, этот код не будет работать, если вы хотите дописать ему порказатель: если Вы попробуете напечатать как \sqrt[b]{a} после использования кода выше, то столкнётесь с тем, что TeX выдаст неправильный вывод. То есть Вы можете таким образом изменить команду квадратного корня только в том случае, если Вы не планируете указывать показатели у корней во всём Вашем документе.

Альтернативный код, позволяющий указывать показатели у корней, представлен ниже:

\usepackage{letltxmacro}

\makeatletter

\let\oldr@@t\r@@t

\def\r@@t#1#2{%

\setbox0=\hbox{$\oldr@@t#1{#2\,}$}\dimen0=\ht0

\advance\dimen0-0.2\ht0

\setbox2=\hbox{\vrule height\ht0 depth -\dimen0}%

{\box0\lower0.4pt\box2}}

\LetLtxMacro{\oldsqrt}{\sqrt}

\renewcommand*{\sqrt}[2][\ ]{\oldsqrt[#1]{#2} }

\makeatother

$\sqrt[a]{b} \quad \oldsqrt[a]{b}$

|

Но стоит учитывать, что этот способ предполагает подключение пакета \usepackage{letltxmacro}.

Ряды и интегралы

[править]Команды \sum и \int создают символы Ряда и Интеграла соответсвенно. Нижний предел задаётся символом "_", а верхний "^". Пример использования Ряда:

\sum_{i=1}^{10} t_i

|

|

или

\displaystyle\sum_{i=1}^{10} t_i

|

|

Пределы для интегралов задаются по правилам такой же нотации, что и для Рядов. Так же важно обозначать дифференциал некоторой величины прямым шрифтом, что достигается командой "\mathrm", и с небольшим отступом от подынтегрального выражения с помощью команды "\,"

\int_0^\infty e^{-x}\,\mathrm{d}x

|

|

Есть много других "больших" команд, которые работают подобным образом:

\sum |

\prod |

\coprod |

|||||

\bigoplus |

\bigotimes |

\bigodot |

|||||

\bigcup |

\bigcap |

\biguplus |

|||||

\bigsqcup |

\bigvee |

\bigwedge |

|||||

\int |

\oint |

\iint[1] |

|||||

\iiint[1] |

\iiiint[1] |

\idotsint[1] |

Что бы использоваться больше интегральных символов, которые не входят в шрифт Computer Modern, подключите пакет esint.

Команда \substack command[1] позволяет использовать два обратных слэша \\ для записи пределов Ряда или интеграла в несколько строк:

\sum_{\substack{

0<i<m \\

0<j<n

}}

P(i,j)

|

|

Если вы хотите, чтобы пределы интеграла были указаны выше или ниже символа, используйте команду \limits:

\int\limits_a^b

|

|

Однако если вы хотите, чтобы это применялось ко ВСЕМ интегралам, то нужно указать параметр intlimits при подключении пакета amsmath:

\usepackage[intlimits]{amsmath}

|

Нижние и верхние пределы в других контекстах, а также другие параметры пакета amsmath связанные с ними, описаны в главе Продвинутая математика.

Для больших интегралов можно использовать пакет bigints [2].

Скобки, фигурные скобки и разделители

[править]Как использовать фигурные скобки в многострочных уравнениях описано в главе Продвинутая математика.

Использование разделителей, таких как скобки, становится важным при работе с чем угодно, кроме самых тривиальных уравнений. Без них формулы могут стать двусмысленными. Кроме того, специальные типы математических структур, такие как матрицы, невозможно представить без разделителей.

Существует множество разделителей, доступных для использования в LaTeX:

( a ), [ b ], \{ c \}, | d |, \| e \|,

\langle f \rangle, \lfloor g \rfloor,

\lceil h \rceil, \ulcorner i \urcorner,

/ j \backslash

|

|

где \lbrack и \rbrack могут использоваться вместо "[" и "]".

Автоматическое определение размеров

[править]Очень часто математические функции будут отличаться друг от друга по размеру, и в этом случае разделители, окружающие выражение, должны изменяться соответственно. Это можно сделать автоматически с помощью команд \left, \right, и \middle. Любой из выше перечисленных разделителей может быть использован в сочетании с этими командами:

\left(\frac{x^2}{y^3}\right)

|

|

P\left(A=2\middle|\frac{A^2}{B}>4\right)

|

Фигурные скобки определяются иначе, с помощью \left\{ и \right\},

\left\{\frac{x^2}{y^3}\right\}

|

|

Если разделитель нужен только с одной стороны выражения, то с другой стороны разделить может быть обозначен точкой (.), что сделает его невидимым.

\left.\frac{x^3}{3}\right|_0^1

|

|

Ручное определение размеров

[править]В некоторых случаях автоматический размер, создаваемый командами \left и \right , может быть отличен от того, что вы ожидаете увидеть, или вам требуется более точно контролировать размеры разделителей. В этом случае могут использоваться команды-модификаторы \big, \Big, \bigg и \Bigg:

( \big( \Big( \bigg( \Bigg(

|

|

Эти команды в первую очередь полезны при работе с вложенными разделителями. Например, при наборе текста:

\frac{\mathrm d}{\mathrm d x} \left( k g(x) \right)

|

|

Мы видим, что команды \left и \right создают разделители такого же размера, что и вложенные в них. Это может создать трудности при чтении записей. Чтобы исправить это, мы пишем:

\frac{\mathrm d}{\mathrm d x} \big( k g(x) \big)

|

|

Ручное определение размеров также может быть полезно, когда уравнение слишком велико, поэтому заканчивается в конце страницы, и должно быть разделено на две строки с помощью команды "align". Хотя команды \left. и \right. можно использовать для автоматического определения размеров разделителей на каждой строке, это может привести к неправильным размерам. Кроме того, нужно использовать ручное определение размеров, чтобы избежать чрезмерно больших разделителей, если между ними появляется \underbrace или аналогичная команда.

Матрицы и массивы

[править]Обычная матрица может быть создана с использованием среды[1]: как и в других табличных структурах, записи задаются по строкам, столбцы разделяются амперсандом (&),а новые строки - двойной обратной косой чертой (\\)

\[

\begin{matrix}

a & b & c \\

d & e & f \\

g & h & i

\end{matrix}

\]

|

|

Чтобы указать необходимость выравнивания столбцов в таблице, используйте знак (*) [3]:

\begin{matrix}

-1 & 3 \\

2 & -4

\end{matrix}

=

\begin{matrix*}[r]

-1 & 3 \\

2 & -4

\end{matrix*}

|

|

Выравнивание по умолчанию - c, но это может быть любой тип столбца, допустимый в среде .

Однако матрицы обычно заключаются в какие-либо разделители, и, хотя можно использовать команды \left и \right, существуют различные другие предопределенные среды, которые автоматически включают разделители:

| Имя среды | Разделитель | Описание |

|---|---|---|

| [1] | по умолчанию центрирует столбцы | |

| [3] | позволяет задать выравнивание столбцов в необязательном параметре | |

| [1] | по умолчанию центрирует столбцы | |

| [3] | позволяет задать выравнивание столбцов в необязательном параметре | |

| [1] | по умолчанию центрирует столбцы | |

| [3] | позволяет задать выравнивание столбцов в необязательном параметре | |

| [1] | по умолчанию центрирует столбцы | |

| [3] | позволяет задать выравнивание столбцов в необязательном параметре | |

| [1] | по умолчанию центрирует столбцы | |

| [3] | позволяет задать выравнивание столбцов в необязательном параметре |

При записи матриц произвольного размера принято использовать горизонтальное, вертикальное и диагональное троеточие (известное как ellipses), для заполнения определенных столбцов и строк. Их можно указать с помощью \cdots, \vdots и \ddots соответственно:

A_{m,n} =

\begin{pmatrix}

a_{1,1} & a_{1,2} & \cdots & a_{1,n} \\

a_{2,1} & a_{2,2} & \cdots & a_{2,n} \\

\vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\

a_{m,1} & a_{m,2} & \cdots & a_{m,n}

\end{pmatrix}

|

|

В некоторых случаях вам может понадобиться возможность более более тонкой настройки выравнивания в каждом столбце или вставка линий между столбцами или строками. Этого можно добиться с помощью среды , которая по сути является математической версией среды [[../Tables#The tabular environment|tabular]], требующей предварительного задания столбцов:

\begin{array}{c|c}

1 & 2 \\

\hline

3 & 4

\end{array}

|

|

Вы можете заметить, что матричный класс сред AMS не оставляет достаточно места при использовании вместе с фракциями, что приводит к выводу, похожему на этот:

Чтобы справиться с этой проблемой, добавьте дополнительный пробел с помощью необязательного параметра в команде \\\:

M = \begin{bmatrix}

\frac{5}{6} & \frac{1}{6} & 0 \\[0.3em]

\frac{5}{6} & 0 & \frac{1}{6} \\[0.3em]

0 & \frac{5}{6} & \frac{1}{6}

\end{bmatrix}

|

|

Если вам нужны "границы" или "индексы" на вашей матрице, обычный TeX предоставляет макрос \bordermatrix

M = \bordermatrix{~ & x & y \cr

A & 1 & 0 \cr

B & 0 & 1 \cr}

|

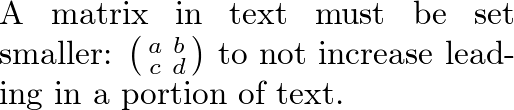

Матрицы в тексте

[править]Чтобы вставить небольшую матрицу и не увеличивать размер начальной строки в строке, содержащей ее, используйте окружение :

A matrix in text must be set smaller:

$\bigl(\begin{smallmatrix}

a&b \\ c&d

\end{smallmatrix} \bigr)$

to not increase leading in a portion of text.

|

Добавление текста в уравнения

[править]Математическое окружение отличается от текстового в плане представления текста. Вот пример попытки представить текст внутри математического окружения:

50 apples \times 100 apples = lots of apples^2

|

|

Есть две заметные проблемы: между словами и цифрами нет пробелов, а буквы выделены курсивом и расположены через большее расстояние, чем обычно. Обе проблемы являются просто артефактами математического режима, поскольку он рассматривает их как математическое выражение: пробелы игнорируются (математика LaTeX использует пробелы в соответствии со своими собственными правилами), и каждый символ является отдельным элементом (поэтому они расположены не так близко, как обычный текст).

Существует несколько способов правильного добавления текста. Типичный способ - обернуть текст с помощью команды \text{...} [1] ( похожая команда \mbox{...}, хотя она вызывает проблемы с нижними индексами в тексте и имеет менее описательное название). Ниже приведен вариант записи с адаптированным кодом уровенения приведенном выше:

50 \text{apples} \times 100 \text{apples}

= \text{lots of apples}^2

|

|

Текст выглядит лучше. Однако между цифрами и словами нет пробелов. К сожалению, их приходится добавлять в явном виде. Существует множество способов добавления пробелов между математическими элементами, но для простоты мы можем просто вставить символы пробела в команды \text.

50 \text{ apples} \times 100 \text{ apples}

= \text{lots of apples}^2

|

|

Форматированный текст

[править]Использование \text прекрасно подходит и позволяет получить простой результат. Тем не менее, существует альтернатива, которая предлагает немного больше гибкости. Возможно, вы помните о командах форматирования font formatting commands, таких как \textrm, \textit, \textbf и т.п. Эти команды форматируют содержимое соответствующим образом, например, \textbf{bold text} делает полужирный текст. Эти команды в равной степени применимы и в математическом окружении для включения текста. Дополнительное преимущество заключается в том, что вы можете лучше управлять форматированием текста, чем с помощью стандартного способа \text.

50 \textrm{ apples} \times 100

\textbf{ apples} = \textit{lots of apples}^2

|

|

Форматирование математических символов

[править]- Смотрите также: w:Mathematical Alphanumeric Symbols, w:Help:Displaying a formula#Alphabets and typefaces and w:Wikipedia:LaTeX symbols#Fonts

Выше было приведено описание возможностей форматирования текста, ниже описаны возможности по форматированию математических выражений. Существует набор команд форматирования, очень похожих на команды форматирования шрифтов, за исключением того, что они специально предназначены для текста в математическом режиме (требуется amsfonts)

| Команда LaTeX | Пример | Описание | Общее применение |

|---|---|---|---|

\mathnormal{…}(or simply omit any command) |

Математический шрифт по умолчанию | Большинство математических обозначений | |

\mathrm{…}

|

Шрифт по умолчанию или обычный шрифт, без выделения. | Единицы измерения, функции в одно слово | |

\mathit{…}

|

Курсивный шрифт | Многобуквенные имена функций или переменных. По сравнению с \mathnormal, слова располагаются более естественно, а числа также выделяются курсивом.

| |

\mathbf{…}

|

Жирный шрифт | Вектора | |

\mathsf{…}

|

Sans-serif | Категории | |

\mathtt{…}

|

Monospace (fixed-width) font | ||

\mathfrak{…}

|

Fraktur | Почти канонический шрифт для алгебр Ли, идеалы в теории колец | |

\mathcal{…}

|

Каллиграфия (только заглавные буквы) | Часто используется для обозначения связок/схем и категорий, используется для обозначения cryptological понятий, таких как алфавит определения (), пространство сообщений (), пространство шифротекстов () и пространство ключей" (); Kleene's ; naming convention in description logic; Преобразование Лапласа () и Преобразование Фурье () | |

\mathbb{…}(requires the amsfonts or amssymb package) |

Blackboard bold (uppercase only) | Used to denote special sets (e.g. real numbers) | |

\mathscr{…}(requires the mathrsfs package) |

Script (только заглавные буквы) | Альтернативный шрифт для категорий и связок. |

Эти команды форматирования можно использовать для всего уравнения, а не только для текстовых элементов: они форматируют только буквы, цифры и греческие буквы в верхнем регистре, а другие математические команды не затрагиваются.

Чтобы выделить строчные греческие или другие символы, используйте команду \boldsymbol [1]; это будет работать только в том случае, если в текущем шрифте существует полужирная версия символа. В крайнем случае есть команда \pmb[1] (Poor Man's Bold, можно перевести как «жирный шрифт для бедных»): она печатает несколько версий символа, слегка смещенных друг относительно друга.

\boldsymbol{\beta} = (\beta_1,\beta_2,\dotsc,\beta_n)

|

|

Чтобы изменить размер шрифтов в математическом режиме, см. раздел [[../Advanced Mathematics#Changing font size|Changing font size]].

Акценты

[править]Что же делать, если закончились символы и шрифты? Следующий шаг - использовать акценты:

a' or a^{\prime} |

a'' |

||

\hat{a} |

\bar{a} |

||

\grave{a} |

\acute{a} |

||

\dot{a} |

\ddot{a} |

||

\not{a} |

\mathring{a} |

||

\overrightarrow{AB} |

\overleftarrow{AB} |

||

a''' |

a'''' |

||

\overline{aaa} |

\check{a} |

||

\breve{a} |

\vec{a} |

||

\dddot{a}[1] |

\ddddot{a}[1] |

||

\widehat{AAA} |

\widetilde{AAA} |

||

\stackrel\frown{AAA} |

|||

\tilde{a} |

\underline{a} |

Цвета

[править]Пакет xcolor, описанный в [[../Colors#Adding_the_color_package|Colors]], позволяет добавлять цвет к нашим уравнениям. Например,

k = {\color{red}x} \mathbin{\color{blue}-} 2

|

|

Единственная проблема заключается в том, что это нарушает стандартное форматирование

вокруг оператора-. Чтобы исправить это, мы заключаем его в окружение\mathbin, поскольку-является бинарным оператором. Этот процесс описан здесь.

Знаки плюс и минус

[править]LaTeX обрабатывает знаки + и – двумя возможными способами. Наиболее распространенным является бинарный оператор. Когда по обе стороны от знака появляются два математических элемента, предполагается, что это бинарный оператор, и поэтому он выделяет некоторое пространство по обе стороны от знака. Альтернативный способ – знаковое обозначение. Это когда вы указываете, является ли математическая величина положительной или отрицательной. Это обычное явление для последнего, поскольку в математике такие элементы считаются положительными, если перед ними не стоит знак -. В этом случае вы хотите, чтобы знак располагался рядом с соответствующим элементом, чтобы показать их связь. Если вы поставили + или - без ничего перед ним, но хотите, чтобы он обрабатывался как бинарный оператор, вы можете добавить «невидимый» символ перед оператором, используя {}. Это может быть полезно, если вы пишете многострочные формулы, и новая строка может начинаться, например, с - или +, тогда вы можете исправить некоторые странные выравнивания, добавив невидимый символ там, где это необходимо.

Знак плюс-минус записывается как:

\pm

|

|

Аналогично существует и знак минус-плюс:

\mp

|

|

Управление горизонтальным расстоянием

[править]LaTeX, безусловно, неплохо справляется с математическим набором - это было одной из главных целей основной системы TeX, которую расширяет LaTeX. Однако не всегда можно рассчитывать на то, что он точно интерпретирует формулы так, как это бы сделали вы. При неоднозначных выражениях она вынуждена делать определенные допущения. Результатом этого, как правило, становится немного неправильный горизонтальный интервал. В таких случаях результат все равно остается удовлетворительным, но перфекционисты, несомненно, захотят "доработать" свои формулы, чтобы интервалы были правильными. Как правило, это очень тонкие настройки.

Бывают и другие случаи, когда LaTeX выполнил свою работу правильно, но вы просто хотите добавить немного пространства, возможно, чтобы добавить какой-нибудь комментарий. Например, в следующем уравнении желательно, чтобы между математикой и текстом оставалось приличное пространство.

\[ f(n) =

\begin{cases}

n/2 & \quad \text{if } n \text{ is even}\\

-(n+1)/2 & \quad \text{if } n \text{ is odd}

\end{cases}

\]

|

|

Этот код выдает ошибки в Miktex 2.9 и не дает результатов, показанных справа. Используйте \mathrm вместо \text.

(Обратите внимание, что этот конкретный пример можно выразить в более элегантном коде с помощью конструкции , предоставляемой пакетом

amsmath, описанным в главе Продвинутая математика).

В LaTeX есть две команды, которые можно использовать в любых документах (не только математических) для вставки горизонтального пространства. Это \quad и \qquad.

\quad - это пробел, равный текущему размеру шрифта. Так, если вы используете шрифт размером 11pt, то пространство, предоставляемое \quad, также будет равно 11pt (по горизонтали, конечно). \qquad дает вдвое больше. Как видно из кода приведенного выше примера, \quad были использованы, чтобы добавить некоторое разделение между математикой и текстом.

Итак, вернемся к тонкой настройке, о которой говорилось в начале документа. Хорошим примером может служить отображение простого уравнения для неопределенного интеграла y относительно x:

Если вы попробуете это сделать, вы можете написать:

\int y \mathrm{d}x

|

|

Однако это не дает правильного результата. LaTeX не учитывает пробел, оставленный в коде для обозначения того, что y и dx являются независимыми сущностями. Вместо этого он объединяет их в одно целое. В этой ситуации \quad было бы излишним - в данном случае нужны небольшие пробелы, которые можно использовать, и LaTeX их предоставляет:

| Command | Description | Size |

|---|---|---|

\,

|

small space | 3/18 of a quad |

\:

|

medium space | 4/18 of a quad |

\;

|

large space | 5/18 of a quad |

\!

|

negative space | -3/18 of a quad |

NB При необходимости вы можете использовать более одной команды в последовательности для достижения большего пространства.

Итак, чтобы исправить текущую проблему:

\int y\, \mathrm{d}x

|

|

\int y\: \mathrm{d}x

|

|

\int y\; \mathrm{d}x

|

|

Негативное пространство может показаться странным, однако его не было бы, если бы оно не имело "некоторого" применения! Возьмем следующий пример:

\left(

\begin{array}{c}

n \\

r

\end{array}

\right) = \frac{n!}{r!(n-r)!}

|

|

Матрицеподобное выражение для представления биномиальных коэффициентов слишком сильно заполнено. Слишком много места между скобками и фактическим содержимым внутри. Это легко исправить, добавив несколько отрицательных пробелов после левой скобки и перед правой скобкой.

\left(\!

\begin{array}{c}

n \\

r

\end{array}

\!\right) = \frac{n!}{r!(n-r)!}

|

|

В любом случае, добавление пробелов вручную следует избегать при любой возможности: это усложняет исходный код и противоречит основным принципам подхода "Что видишь, то и подразумеваешь". Лучше всего определить несколько команд, используя все необходимые пробелы, и тогда, когда вы используете свою команду, вам не придется добавлять другие пробелы. В дальнейшем, если вы передумаете насчет длины горизонтального пространства, вы сможете легко изменить ее, изменив только ту команду, которую вы определили ранее. Приведем пример: вы хотите, чтобы буква d в интеграле dx была набрана римским шрифтом и отстояла от остальных на небольшой промежуток. Если вы хотите напечатать интеграл типа \int x \, \mathrm{d} x, вы можете задать команду следующим образом:

\newcommand{\dd}{\mathop{}\,\mathrm{d}}

|

в преамбуле вашего документа. Мы выбрали \dd только потому, что он напоминает букву "d", которую он заменяет, и его быстро набирать. Таким образом, код для вашего интеграла станет \int x \dd x. Теперь, когда бы вы ни писали интеграл, вам просто нужно использовать \dd вместо "d", и все ваши интегралы будут иметь одинаковый стиль. Если вы передумаете, то просто измените определение в преамбуле, и все ваши интегралы изменятся соответствующим образом.

Ручное указание стиля формулы

[править]Чтобы вручную отобразить фрагмент формулы с помощью текстового стиля, окружите фрагмент фигурными скобками и добавьте к нему префикс \textstyle. Скобки нужны потому, что макрос \textstyle изменяет состояние рендерера, отображая всю последующую математику в текстовом стиле. Скобки ограничивают это изменение состояния только фрагментом, заключенным в них. Например, чтобы использовать стиль текста только для символа суммирования в сумме, нужно ввести

\begin{equation}

C^i_j = {\textstyle \sum_k} A^i_k B^k_j

\end{equation}

|

То же самое в виде команды будет выглядеть следующим образом:

\newcommand{\tsum}[1]{{\textstyle \sum_{#1}}}

|

Обратите внимание на дополнительные скобки. Одного набора вокруг выражения будет недостаточно. Это приведет к тому, что вся математика после \tsum k будет отображаться с помощью текстового стиля.

Чтобы отобразить часть формулы с помощью стиля display, сделайте то же самое, но вместо него используйте \displaystyle.

Продвинутая математика: Пакет AMS Math

[править]AMS (American Mathematical Society) - это мощный математический пакет, который создает более высокий уровень абстракции по сравнению с математическим языком LaTeX. Работа с формулами может быть значительно упрощенна при использовании данного пакета. Некоторые команды, которые выводит amsmath, сделают другие простые команды LaTeX устаревшими: чтобы сохранить согласованность в конечном выводе, вам лучше использовать команды amsmath, когда это возможно. Если вы это сделаете, то вы получите достаточно элегантный результат, не беспокоясь о выравнивании и других деталях, сохраняя при этом исходный код читабельным. Если вы хотите его использовать, вам нужно добавить в преамбулу следующий код:

\usepackage{amsmath}

|

Ввод точек в формулы

[править]amsmath также определяет команду \dots, которая является обобщением существующей команды \ldots. Вы можете использовать \dots как в текстовом, так и в математическом режиме, и LaTeX заменит его тремя точками "…", но в зависимости от контекста он решит, следует ли помещать его внизу (например, { {LaTeX/LaTeX|code=\ldots}}) или по центру (например, \cdots).

Точки

[править]LaTeX предоставляет несколько команд для вставки точек (эллипсов) в формулы. Это может быть особенно полезно, если вам приходится печатать большие матрицы, опуская элементы. Ниже приведены основные команды LaTeX, связанные с точками:

| Код | Вывод | Комментарий |

|---|---|---|

\dots |

общие точки (многоточие) для использования в тексте (в том числе вне формул). Он автоматически управляет пробелами до и после себя в соответствии с контекстом. Это команда более высокого уровня. | |

\ldots |

вывод аналогичен предыдущему, но автоматическое управление пробелами отсутствует. Работает на более низком уровне. | |

\cdots |

эти точки центрируются относительно высоты буквы. Существует также оператор двоичного умножения \cdot, упомянутый ниже.

| |

\vdots |

вертикальные точки | |

\ddots |

диагональные точки | |

\iddots |

обратные диагональные точки (требует пакет

mathdots) | |

\hdotsfor{n} |

для использования в матрицах он создает строку точек, охватывающую n столбцов. |

Вместо использования \ldots и \cdots вам следует использовать семантически ориентированные команды. Это позволяет на лету адаптировать ваш документ к различным соглашениям, например, в случае, если вам придется отправить его издателю, который настаивает на следовании домашним традициям в этом отношении. Обработка различных типов по умолчанию соответствует соглашениям Американского математического общества.

Запишите уравнение с выравниванием среды

[править]Как написать уравнение в среде align с пакетом amsmath описано в Продвинутая математика.

Список математических символов

[править]Ниже перечислены все предопределенные математические символы из пакета \TeX\. Другие символы можно получить из дополнительных пакетов.

| Символ | Код | Символ | Код | Символ | Код | Символ | Код | Символ | Код | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

<

|

>

|

=

|

\parallel

|

\nparallel

| |||||||||

\leq

|

\geq

|

\doteq

|

\asymp

|

\bowtie

| |||||||||

\ll

|

\gg

|

\equiv

|

\vdash

|

\dashv

| |||||||||

\subset

|

\supset

|

\approx

|

\in

|

\ni

| |||||||||

\subseteq

|

\supseteq

|

\cong

|

\smile

|

\frown

| |||||||||

\nsubseteq

|

\nsupseteq

|

\simeq

|

\models

|

\notin

| |||||||||

\sqsubset

|

\sqsupset

|

\sim

|

\perp

|

\mid

| |||||||||

\sqsubseteq

|

\sqsupseteq

|

\propto

|

\prec

|

\succ

| |||||||||

\preceq

|

\succeq

|

\neq

|

\sphericalangle

|

\measuredangle

| |||||||||

\therefore

|

\because

|

| Символ | Код | Символ | Код | Символ | Код | Символ | Код | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

\pm

|

\cap

|

\diamond

|

\oplus

| |||||||

\mp

|

\cup

|

\bigtriangleup

|

\ominus

| |||||||

\times

|

\uplus

|

\bigtriangledown

|

\otimes

| |||||||

\div

|

\sqcap

|

\triangleleft

|

\oslash

| |||||||

\ast

|

\sqcup

|

\triangleright

|

\odot

| |||||||

\star

|

\vee

|

\bigcirc

|

\circ

| |||||||

\dagger

|

\wedge

|

\bullet

|

\setminus

| |||||||

\ddagger

|

\cdot

|

\wr

|

\amalg

|

| Символ | Код | Символ | Код | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

\exists

|

\rightarrow or \to

| |||

\nexists

|

\leftarrow or \gets

| |||

\forall

|

\mapsto

| |||

\neg

|

\implies

| |||

\subset

|

⟸ | \impliedby

| ||

\supset

|

\Rightarrow or \implies

| |||

\in

|

\leftrightarrow

| |||

\notin

|

\iff

| |||

\ni

|

\Leftrightarrow (preferred for equivalence (iff))

| |||

\land

|

\top

| |||

\lor

|

\bot

| |||

\angle

|

and | \emptyset and \varnothing[1]

| ||

\rightleftharpoons

|

| Символ | Код | Символ | Код | Символ | Код | Символ | Код | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| or \mid (difference in spacing)

|

\|

|

/

|

\backslash

| |||||||

\{

|

\}

|

\langle

|

\rangle

| |||||||

\uparrow

|

\Uparrow

|

\lceil

|

\rceil

| |||||||

\downarrow

|

\Downarrow

|

\lfloor

|

\rfloor

|

Примечание: Чтобы использовать в LaTeX греческие буквы, которые имеют тот же вид в латинском алфавите, просто используйте латинские: например, A вместо Alpha, B вместо Beta и т. д.

| Символ | Код | Символ | Код | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| и | A и \alpha

|

и | N и \nu

| |

| и | B и \beta

|

и | \Xi и \xi

| |

| и | \Gamma и \gamma

|

и | O и o

| |

| и | \Delta и \delta

|

, и | \Pi, \pi и \varpi

| |

| , and | E, \epsilon и \varepsilon

|

, и | P, \rho и \varrho

| |

| и | Z и \zeta

|

, и | \Sigma, \sigma и \varsigma

| |

| и | H и \eta

|

и | T и \tau

| |

| , и | \Theta, \theta и \vartheta

|

и | \Upsilon и \upsilon

| |

| и | I и \iota

|

, , и | \Phi, \phi и \varphi

| |

| , и | K, \kappa и \varkappa

|

и | X и \chi

| |

| и | \Lambda и \lambda

|

и | \Psi и \psi

| |

| и | M и \mu

|

и | \Omega и \omega

|

| Символ | Код | Символ | Код | Символ | Код | Символ | Код | Символ | Код | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

\partial

|

\imath

|

\Re

|

\nabla

|

\aleph

| |||||||||

\eth

|

\jmath

|

\Im

|

\Box

|

\beth

| |||||||||

\hbar

|

\ell

|

\wp

|

\infty

|

\gimel

|

^ Не предопределены в LATEX 2. Используйте один из пакетов latexsym, amsfonts, amssymb, txfonts, pxfonts или wasysy

| Символ | Код | Символ | Код | Символ | Код | Символ | Код | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

\sin

|

\arcsin

|

\sinh

|

\sec

| |||||||

\cos

|

\arccos

|

\cosh

|

\csc

| |||||||

\tan

|

\arctan

|

\tanh

|

||||||||

\cot

|

\arccot

|

\coth

|

Если в LaTeX нет команды для математического оператора, который вы хотите использовать, например \cis (cосин плюс i, умноженный на sine), добавьте в преамбулу:

\DeclareMathOperator\cis{cis}

Затем вы можете использовать \cis в документе так же, как \cos или любой другой математический оператор.

Резюме

[править]Как вы начинаете видеть, математические вычисления иногда могут быть непростыми. Однако, поскольку LaTeX обеспечивает такой большой контроль, вы можете получить математическую верстку профессионального качества с относительно небольшими усилиями (конечно, после того, как вы немного попрактикуетесь!). Можно было бы продолжать изучать математические темы, потому что они кажутся потенциально безграничными. Однако с этим руководством вы сможете достаточно справиться.

* introduce symbols from [2]

|

Notes

[править]- ↑ а б в г д е ё ж з и й к л м н о требуется пакет amsmath

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/2268/6219

- ↑ а б в г д е требуется пакет mathtools

Further reading

[править]- meta:Help:Displaying a formula: Wikimedia uses a subset of LaTeX commands.

External links

[править]- detexify: applet for looking up LaTeX symbols by drawing them

- amsmath documentation

- LaTeX - The Student Room

- The Comprehensive LaTeX Symbol List

- MathLex - LaTeX math translator and equation builder

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{n}]{1+x+x^{2}+x^{3}+\dots +x^{n}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/74a7b5d7b8b7c0651bcbbd83c02ca86dbf87789b)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{b}]{a}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3ceeccbbf1609652afdb8d84d33552cd2731bb0d)

![{\displaystyle (a),[b],\{c\},|d|,\|e\|,\langle f\rangle ,\lfloor g\rfloor ,\lceil h\rceil ,\ulcorner i\urcorner ,/j\backslash }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/65ff76385ff85daf87ceef4734e98932ec5fd772)

![{\displaystyle [\,]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c5444b5227fcebf7e7cbb9ee114af1373f6a2e95)

![{\displaystyle M={\begin{bmatrix}{\frac {5}{6}}&{\frac {1}{6}}&0\\[0.3em]{\frac {5}{6}}&0&{\frac {1}{6}}\\[0.3em]0&{\frac {5}{6}}&{\frac {1}{6}}\end{bmatrix}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4989d4433782a036095cdf274ee636c5f783125c)